Preventing human trafficking and exploitation is the ultimate goal of international agreements, national policies and hundreds, if not thousands, of counter-trafficking organisations.

We know this is not an easy task. Human trafficking and exploitation operates as a dynamic complex system across the world. How, in all good faith, can we intervene in structures and systems of economy, the law, social systems, communities, families and in individual lives to prevent modern slavery from happening?

We can’t pretend to have found all the answers in a Modern Slavery PEC research project which we published this week, but I think we have come some way in articulating the challenge and identifying some solutions. The research explored what does or could work in the prevention of two forms of modern slavery among adults in the UK: labour and sexual exploitation. It examined what has been tried in prevention programmes, projects and initiatives, and considered promising practice.

The project drew on the collective skills and knowledge of the UK Black and Minority Ethnic Anti-Slavery Network (BASNET), the West Midlands Anti-Slavery Network (WMASN) and the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield.

These are the five critical things we learned:

1. Prevention is about avoiding and minimising the bad and promoting the good

Our research with people working in the counter-slavery sector, survivors of exploitation and a review of the literature brought us to a definition of prevention that had not been previously articulated:

Prevention is an on-going process of avoiding and minimising exploitation and harm. This can be achieved by intervening before harm occurs, by intervening early and by treating harms. It also includes action to prevent re-exploitation and re-trafficking. Prevention includes enabling people to exercise choice and control over their lives and to thrive.

This definition of prevention could guide future prevention strategy and action plans at national and local levels. It fits with a public health approach to modern slavery; a framework with prevention at its core. It highlights both a traditional prevention message – to stop bad things from happening and minimising harms – and an optimistic, health promoting one; it should promote healthy and fulfilling lives.

2. Prevention should be seen as a ‘whole system’

Prevention activity is not constituted of discrete parts. Interventions interconnect to create a ‘whole system’ which may be more or less complete or robust. We found a lot of activity to prevent on-going harm once people had already been exploited. We need a more complete system that acts to prevent harm before it is done. Consultation panels highlighted how policy, legal systems and law enforcement have great power to prevent exploitation and harm from happening in the first place but that this potential had not been realised in the UK to date.

3. There are 12 principles of prevention intervention

To maximise the impact and minimise the risks of generating or reinforcing harm through prevention programmes, interventions should follow a clear set of principles. Through our research and discussions with people with lived experience we identified twelve of them, which should be used in combination with the Human Trafficking Foundation’s Survivor Care Standards.

Our consultation panels pointed to the importance of overlooked aspects of the prevention landscape such as cultural competency or cultural safety and working with affected communities to build trust. We need bold and brave conversations across the sector to ensure we put these principles into practice.

4. We found 25 different types of prevention activity across the UK

This was more than we expected. When prevention is viewed in broad terms, as the definition suggests, we were able to uncover a large range of efforts (not including policy) to preventing exploitation and harm. We found that training and education and awareness-raising campaigns were most common and most tested, but had largely limited effects.

We need to expand our evaluative effort to ensure that prevention strategies are not reliant on this small knowledge base; awareness-raising and training and education are just a small part of the picture.

5. We identified five ‘pathways’ to prevention - key ways in which interventions are expected to work - across these 25 intervention types.

These are 1. Access to the fundamental things in life; 2. Developing literacy of the problem; 3. Developing power and control among survivors and affected communities, 4. Deterring and disrupting perpetration, 5. Preventing exploitation in partnership.

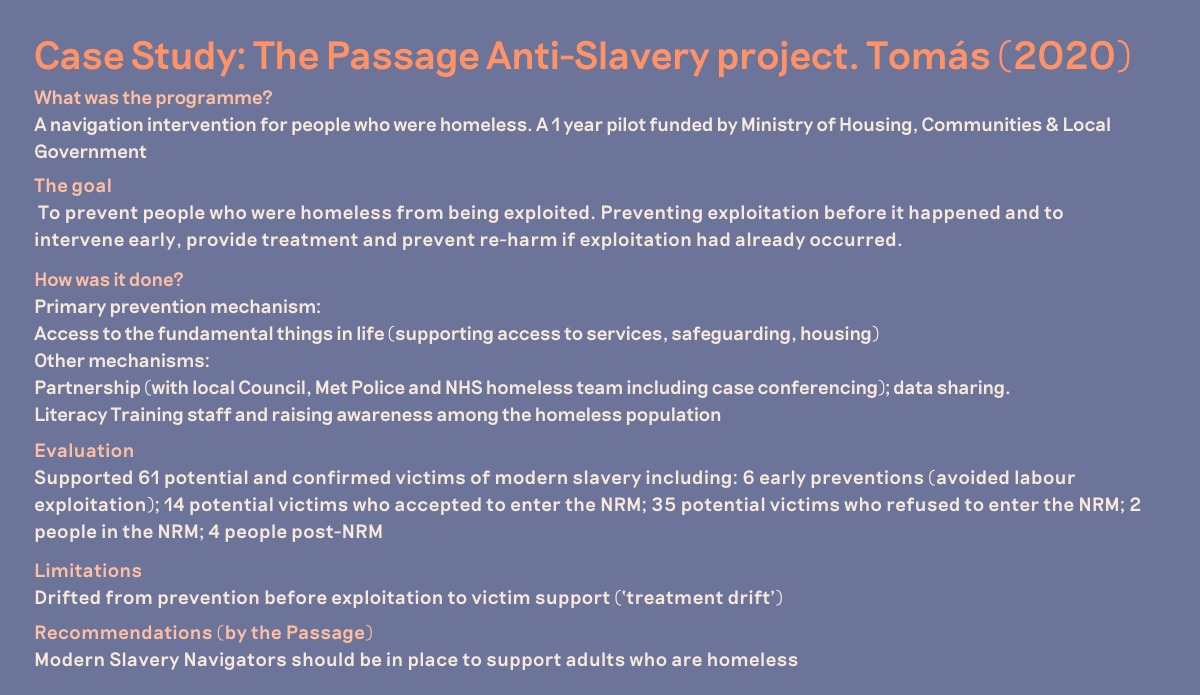

Many of the interventions we looked at included more than one pathway to prevention. It was a complex picture throughout. This example from the homelessness charity The Passage illustrates the point:

Good prevention programmes should take into account all these pathways and develop holistic prevention strategies based on principles developed by our research. In particular, they should consider how to avoid harm in the first place and include affected communities and people with lived experience in the creation of prevention interventions.

We need to change the understanding and approach to prevention to treat it in the holistic way and use the ‘whole system’ approach, addressing all stages of exploitation.

This project is just part of the prevention discussion. The fact we spent a lot of time in our consultation panels discussing the very notion of prevention highlighted how challenging it is but also how strong is the desire to act.

The research is intended guide us towards a clearer picture of what that work looks like and how to do it well.

Liz Such on behalf of the full research team – Habiba Aminu, Amy Barnes, Kate Hayes (ScHARR), Modupe Debbie Ariyo (BASNET) and Robin Brierley (WMASN). Contact e.such@sheffield.ac.uk.